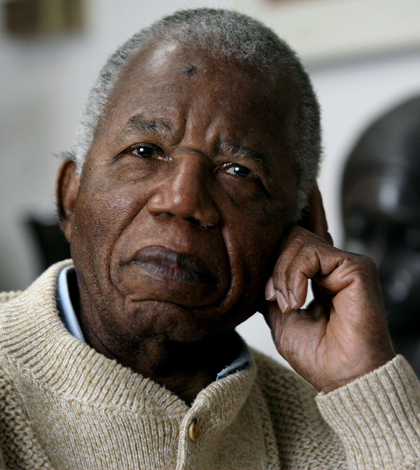

By Chika Unigwe, Ph.D

In his last book, There Was a Country, Achebe writes: ‘As a writer I believe that it is fundamentally important, indeed essential to our humanity, to ask the hard questions, in order to better understand ourselves and our neighbours.’ This role of the writer was one Achebe was very committed to.

It informed his writing starting with Things Fall Apart, his best known work, published in 1958 at a time when issues of identity and nationhood were urgent on the African continent to his latest book which explores the ways the leadership of Nigeria has failed Nigerian citizens. But it was not just in writing that Achebe asked the hard questions. He lived it too. An ardent believer in the value of speaking truth to power, Achebe was a fearless, vocal critic of Nigeria’s failed governments.

In 2004 and 2011 he rejected to accept the National Award given him by the Obasanjo government and the Goodluck Jonathan government respectively. Mincing no words in explaining why it was against his conscience to accept the award, Achebe wrote to Obasanjo, “Nigeria’s condition today under your watch is, however, too dangerous for silence. I must register my disappointment and protest by declining to accept the high honour awarded me in the 2004 Honours List.” In 2011, he wrote to Goodluck Jonathan “the reasons for rejecting the offer when it was first made have not been addressed let alone solved.’ He taught me by the way he lived that integrity is always, always possible. As a writer, Achebe was one of my earliest role models.

I remember reading Things Fall Apart at an age when my literary fare consisted mostly of books by Enid Blyton, and school taught me nothing of pre-colonial Igbo land. I loved the simplicity of the writing. But on a deeper level, that book opened up to me a whole new world at an age I was learning at school that Mungo Park ‘discovered’ the River Niger and that my forefathers were ‘heathen savages’ saved by colonization. It showed me that history taught in schools was not always accurate, and gave me the hunger to seek my history. More importantly, it gave me permission to tell my own story, my own way.

Achebe is dead but he lives. In his works, and in the works of all the writers he inspired all over the world.